How can we teach children to pray?

Firstly, it’s necessary to know and understand that children are not adults. The worldview of children differs quite strongly from that of adult’s. Adults have already tried and experienced much in this life. Figuratively speaking: many times they have fallen and many times gotten up. For children life presents itself in bright colors. The world is enormous and miraculous, and unknown. Every day and every second children are like Christopher Columbus—sailing to discover their own America.

And from another side, children quite strongly differ from adults intellectually, psychologically, and physically. An adult is experienced, but already with a mind downtrodden and preoccupied with problems. A child’s mind is much sharper; he is like a sponge, absorbing information and more quickly processing it. Adults are sturdier and more patient; children are more impulsive, quicker, and more emotional, but tire more quickly. So, for example, as teachers of young students know, the active stage of receptivity during lessons for students seven-ten years old is no more than fifteen minutes. “To pour” more knowledge into their light heads is meaningless. They won’t receive it. As a rule, teachers should then change the activity—from intellectual to physical (for example, gymnastics). After five-ten minutes of muscular exercises the kids are ready to learn again.

We must also know that children and teenagers are different, and what would be interesting to a five-year-old won’t entice a third-grader, and what would be interesting to a third-grader won’t be entertaining for an eleventh-grader. Each age group needs its own special approach in light of the intellectual, emotional, and hormonal-physiological features of its development.

As always in a child’s upbringing, so with prayer, Orthodoxy offers to parents and teachers the method of the “golden mean.” We shouldn’t overly coddle a child, to indulge his weaknesses and burgeoning passions, but it’s also not worth it to raise children with excessive strictness and rigidity. It can break down and he will become embittered and pull back from the studies imposed upon him. This is how it happened, for example, with Chekhov. His father made little Anton sing in the church choir, right down to a beating. In the end, Anton Pavlovich developed a quite complicated relationship with religion. Coercion, whether physical or mental, never led to any good. We must remember, rather, the main truth of pedagogy. Children more often absorb not what we’re saying to them, but rather how we conduct ourselves in life, and they copy our behavior. So we see here a confirmation of the principle: Faith without works is dead (Jas. 2:26). A child measures our faith by our works and examines how far they correspond to our words.

It is best of all to being the work of prayer with an explanation. We mustn’t impose upon a child some rigid imperative: “They say you should, and that’s it.” “Read from here to there, and until you’ve read it all you can’t leave the room”—no. God does not love coercion. We should explain, guided by the experience of the Church, the Holy Fathers, and our own lives, why it’s necessary to pray. Who is the Lord? Why is He unseen? Why does He listen to our prayers? It’s important to answer a child’s questions, to adapt to his perception of the world, including in prayer. I teach in Sunday school. Believe me, children have very many questions regarding the faith, and often quite unexpected and rather interesting ones.

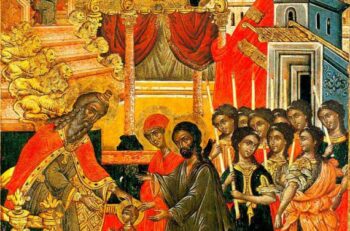

For instance, it might be enough to teach preschool children, perhaps, how to properly make the Sign of the Cross, and explain what is the Sign of the Cross, or how to kiss icons. Sometimes it’s enough just to take them to church, show them an icon and say: “It’s God!” From there their personal path to God begins. And we should accustom our youths to wearing a Cross necklace.

My priestly experience shows that it’s necessary to bring kids to church more often that they wouldn’t be afraid of the “strangeness” of the church or the unconventional appearance (for the modern world) of the priest.

You should also teach children an abridged form of the prayer rule so as not to exhaust them, but to, on the contrary, awaken in them an interest in prayer and attention to the words. It’s good to pray with them to answer all their questions afterwards.

Thus, for example, the morning or evening prayer rule for children could consist of a “cap,” that is, the beginning: from “In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen” up to and including “Our Father.” Then you could add the prayer to your holy Guardian Angel and the Most Holy Theotokos and the child’s patron saint, and that’s enough. In this case it’s important that less is more. Let children read less prayers but with heartfelt attention, rather than more with straining and vexation. You can increase their prayer rule with age, not abruptly and all at once, but slowly and gradually. Memorize certain prayers by heart with your child, like poetry. For example, “Our Father” is the main prayer of Christianity. You should also explain to your child the meaning of each line of this great prayer. You can also learn with them some short prayer to your Guardian Angel, the Most Holy Theotokos, or your Heavenly patron, or, for example “O Heavenly King” for before and after studying. But don’t overload the child too much. Today we have special prayer books just for children.

With an older son or daughter you can analyze the Symbol of Faith (the Creed) for Church members, to memorize it. After all, it itself represents a gathering of the main dogmas (laws) of the Orthodox faith.

You can, of course, dear brothers and sisters, implement strictness and rigidity in raising a child, that he might feel your authority. But you must do so with love without anger or irritation. Generally, it’s best not to begin any undertaking with anger and malice. Nothing good can come of it. It’s better to keep quiet, go off to the side, pray, calm down, and maybe even ask forgiveness, only then beginning your work.

Often a priest has to hear something like this: “When my child was young he went to church, but as an adult he stopped.” We must remember that the adolescent and teenage years are a very difficult time. It’s when their personality and character is developed, it’s a time of reevaluating authority, a time of sexual development. And often with all this people must figure themselves out in order to build their own futures. Here the parents and Grandma and Grandpa can help with the most important thing—by praying for him and by good advice, but not by pressure and authoritarianism. Let your teenager work out his own problems, but also feel that you, his parent, are his good friend to whom he can always turn for help and advice in difficult times.

Our task is to pray, be patient, wait and show our children an example of a godly life. And believe they will at some point return to the Church—return consciously, in maturity, and forever.

From personal experience, I, as an example, always preserved in my heart this recollection: my great grandmother took me to a huge and bright church when I was three, carried me to the radiant chalice, to the batiushka in golden robes… I carried this memory with me throughout my entire young life, and it subsequently helped me to make the right choice. Your sons and daughters will travel their own particular paths in life, but you know that the foundation laid in their souls is true. They will fall and make the same mistakes you did in your youth, but they will be their own. And they will get up to go on. But upon them, in their inner hearts’ horizon, will shine the star of Orthodoxy, carrying them through life.

Only try from a young age to instill in them, with God’s help, love for prayer. It is a journey, and its boat will undoubtedly guide us to God.